The following is one of the papers I have been working on for my English Composition 1-C class. The format of this site isn’t allowing indentation, pardon that. And please pardon typos (especially tricky German words!), still a work in progress.

Degeneracy and the Homoeroticism of National Socialist Visual Culture

OR

Who Are You Calling a Degenerate?

When Michaelangelo’s David was placed upon its pedestal on the 8th of September 1504 in the public square of the Palazzo della Signoria, it was, to the Hellenic minded Florentines a testament to their aspirations and their civic pride. It was also quite sexy. The Florentines looked to a golden past, the grandeur of the classical world, a time and place where heroic male nudes such as the Discobolus and the Farnese Herakles were the aesthetic and political manifestations of the Athenian polis. Perhaps it is unsurprising that 435 years later, Hitler’s favorite sculptor, Arno Breker, also looked to ancient Greece when he presented his equally monumental Bereitschaft (Readiness). The classical world would be, for the National Socialists, a rich resource, one that they would adapt (and degenerate) to suit their malevolent agenda.

Arno Breker

Bereitschaft (Readiness)

1937, bronze, formerly at the Zeppelinfeld, Nuremberg

Hitler’s manifest obsession with social order, conformity, degeneracy, racial purity and the perfect Aryan youth might lead one to wonder what repressed desires he harbored. One of Hitler’s first actions upon ascending to power as chancellor in 1933 was to codify what was and was not acceptable aesthetic expression for the Aryan Völk. In his desire to separate artistic wheat from chafe, “wholesome” German art and that of the Entartete Kunst (degenerate art), Hitler turned to an imagined academic neo-classical precedent, one that suited his concrete comprehension of what constituted as art. But as Hitler purged the world of the degenerate was he wrestling with the degenerate within? By exploring the aesthetic precedent set by 19th c. German neo-classical revivalism, its impact upon the German people, Hitler’s role in that development and its tragic collision with Modernism, one can better determine whether Hitler’s visual dictates merely reflected bourgeois sensibilities or were in fact more complicated.

Devastated by the First World War, the Germans turned to the Greeks to console their collective grief. For example, they turned to the 5th century BCE Greek sculptor, Polyclitus, recasting his poetic Doryphoros, (Speerträger -Spear-bearer) into bronze to commemorate those fallen during the Great War. While the new bronze (formerly at the University of Munich) may appear a bit too shiny and expressionless to the modern eye, it did represent hope to a country ravaged by war. As A.J. Mangan states in his Shaping the Superman: Fascist Body as Political Icon-Aryan Fascism the “bronze,cleansed, healthy body ensured the sound state” (114); Germans of the Weimar Republic turned to the familiar (and sensuous) heroic male nude in their darkest hour. Soon after, with malevolent intention, Hitler would also turn to this model.

Speerträger as it appears to day;ironically his spear was lost in the bombings. Link to source and further info here: https://www.en.uni-muenchen.de/news/spotlight/2015_articles/doryphoros.html

Turning back to the Hellenic period has deep roots. The 18th century German art historian and archeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann, a well-regarded Hellenist, relentlessly advocated for the classical model to be applied to every branch of the arts. As an esteemed proponent of the German neo-classical movement, Winckelmann, as Manyan points out, felt the model of the heroic male nude represented “symbols of masculinity [and ] the nation…their image was one of serenity, self restraint and self sacrifice” (113). What at first were allegorical figures appropriate for the German people, they would be degenerated as Germany forsook Athens for Sparta.

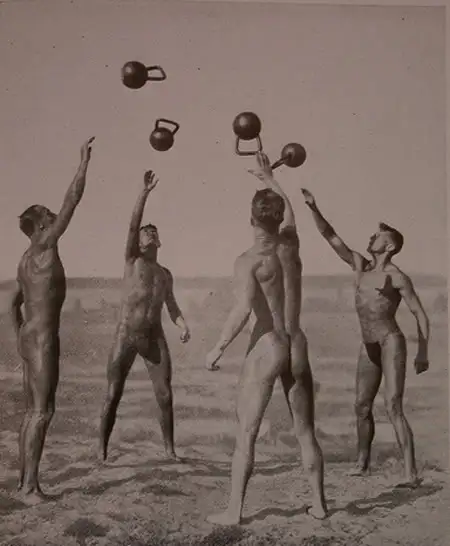

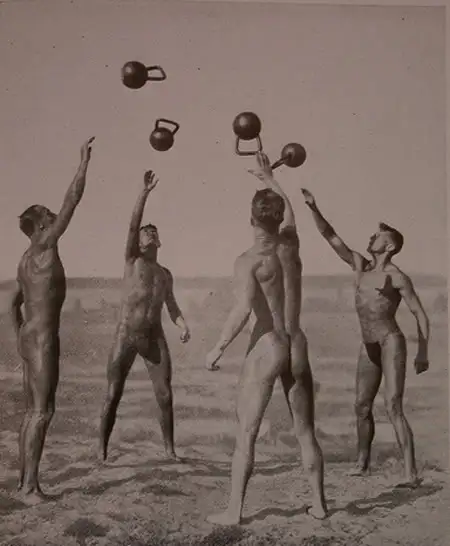

The German public turned to an imagined past in a variety of ways. In 1896 the German Youth Movement would emerge with an emphasis upon scouting groups devoted to wandervogul -traipsing about the glorious countryside. As Mangan claims these outings represented “nostalgia for Grecian icons with love of nature and worship of the sun” (115). This love of sun and light would soon find expression in that other well-known Teutonic obsession, nudism.

Germany, 1916

Source: http://www.hippy.com/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=243

The cult of the nude body, of the sun and of light had roots in a desire to combat the excesses of an increasingly industrialized world, one that wrought havoc upon the halcyon countryside and caused nationalistic existential angst. As the British Arts and Crafts movement turned to an idealized medieval utopia as an inspiration for social and aesthetic reform, the Germans turned to the regenerative light of Apollo. What better way to absorb this healing light and warmth, than to shed the garments of the material world that had encumbered both body and soul? Nudism, or more euphemistically “naturism”, allowed the German people an opportunity “to obtain, in the face of the ravages of industrialization…restoration of life in harmony with nature” according to Mangan(121). This desire found visual expression in the fine and the applied arts. The painters Hans van Marées (1837-1887) and Arnold Böckler (1877-1901) were so well known in their symbolist approach to the classical figure they were regarded as the “German Romans”. The artist and illustrator Hugo Höppener (1868-1948), known as Fidus (who will be explored later in this paper) would further explore the links between the heroic male nude, nature and regeneration.

Hans von Marées

Die Liebensalter

1877-78

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Another example of the links between the Grecian ideal youth, the German polis and ultimately fascist symbolism is not only to be found in the sun kissed meadow but in the dank gymnasium. Specifically in the cult of body building, which even until recently, was considered by the English speaking world as a Teutonic obsession(remind oneself of the beauty and power of the young Austrian Arnold Schwarzenegger). So strongly identified was this link between sculpted male pulchritude and the German training tradition that Kenneth R. Dutton, in his The Perfectable Body:The Western Ideal of Male Physical Development, emphasizes that the 19th century “celebrated [non-German] strongman-poser Louis Hart often billed himself as Ludwig Hardt in order to suggest a German ancestry.” (203). From the posing platform to the 1936 Berlin Olympic games, Germans were ambivalent as to what the male body represented: Apollonian ideals or Spartan fascism. After the (humiliating) devastation of the First World War, this division was made startlingly clear by two teams of bodybuilders who held manifestly contradictory creeds, the Workers Gymnastics League and the German Gymnasts Association.

The Worker’s Gymnastics League, known as the “democratic” gymnasts, were as Dutton explains, an organization that “stood for social justice, liberty and progress”; whereas the German Gymnasts ‘Association (Deutche Turnerschaft) “espoused the cult of the Kaiser, the struggle against Social Democracy, the greatness of the Reich…” (205). The proto fascists sought a balm for their wounded nationalism, that quest led to searching for a scapegoat; the scapegoat would of course be non-Aryan. The urban dwelling Jew would be an ideal scapegoat, for as Dutton asserts, he could be “blamed for the physical and moral degradation of society.” (206). The Jew, to the fascist mind, represented an urban, capitalist elite who sought to contaminate the unsullied Völk.

Post war Germany, psychologically shell-shocked also found itself financially devastated. Amidst the Sturm und drang , the still recovering German people were entertained by what would soon be an unheard of phenomenon, a Jewish übermensch , the strongman Sigmund Breitbart (1893-1925) who went by the stage name der Eisenkönig (the Iron King) for his ability to tear through iron chain. Proudly Jewish, Dutton informs us of Breitbart’s audacity in his posing and flexing before a stage backdrop that prominently featured a Star of David (206). This being the early teens and twenties, the Iron King would soon be embattled by early Nazi supporters; so much so, the Jewish Superman required bodyguards. One might safely assume that Breitbart, loud, proud and Yiddish would align himself with the Worker’s Gymnastics League (Arbeiterturnerbund) .

Sigmund Breitbart 1893-1925

The heroic male nude, whether glorified by Breker or praised by Hitler in nationalistic bombast would very soon be as defining a motif as the eagle and the swastika to the Third Reich. An allegorical figure meant to represent rebirth and vitality of the nation was transformed into a symbol of a fierce and unrelenting war machine.

In spite of the growing anti-Semitism and the increasingly heated rhetoric of the newly emerging National Socialists party, pre-fascist Germany was exploding with new art and ideas. The German Expressionist Max Beckman (1884-1950) was enjoying well-earned praise at home and especially abroad, in spite of the oppressive clouds that were gathering over Berlin. In 1932, the Berlin Neue Nationalgalerie devoted a gallery to his work. In 1933 he finishes his seminal tryptich Departure. Then, that same year, the Nazi Party closed the Beckman Room; the atmosphere in Germany was becoming increasing oppressive for Beckman. A day prior to the state sponsored propagandist exhibition Entartete Kunst was to open, Beckman listened to Hitler’s terrifying radio address. After having had endured such humiliation, much of his work was confiscated by the state from public collections: in total 28 paintings, 560 watercolors, drawings and prints; 21 pieces would be up for public ridicule in the aforementioned Entartete Kunst exhibition. With little more than the coats on their backs, Beckman and his wife Quappi leave Germany to never return again. In his excellent biography of the artist Max Beckman:1884-1950 The Path to Myth, Richard Spieler quotes Beckman’s account of this harrowing period before fleeing to the relative safety of Amsterdam:”The last five year have been a terrible strain for me and I did not actually expect to survive them, it was a dire gamble.” (123). It was a gamble that paid off. His magnificent Departure held pride of place in New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Max Beckman

Departure

MOMA link:

http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=78367

The 588 works of Beckman’s art confiscated by the Third Reich weren’t the only pieces looted in their zeal for Aryan purity (and to fill the party’s coffers). Prior to the National Socialists ascending to power, the German cultural elite was at the forefront in appraising, collecting and promoting modernist art, German Expressionism in particular. Stephanie Barron curator of the 1991 reconstruction of Entartete Kunst at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and author/editor of the exhibition companion catalog Degenerate Art: the fate of the avante-garde in Nazi Germany, points out that from 1919 to 1939 German museums were enthusiastically supporting modernist work, frequently making museum purchases directly from the artists’ studio. These acquisitions are perhaps best examined during the tenure of Paul Ortwin Rave, curator at the above-mentioned Berlin Nationalgalerie in the 1930’s. His influence was broad and far from nationalistic. For in addition to patronizing Beckman and the works of Beckman’s fellow German artists, Rave promoted the Impressionists, Post Impressionists and other foreigners including purchasing work of the Belgian artist James Ensor. Yet it was Rave’s concentration upon German works that was responsible in promoting the esteem of German Expressionism to world at large (13).

It is important to note that the promotion and support of modernist art was indeed often, as Hitler claimed, an elite pursuit. As it is today, the discerning class generally appreciates art best. For much of the German public, modernist art was enigmatic, finding the work confounding and troubling on the heels of 19th century German Romanticism. Hitler shared the people’s disdain for new work. His aesthetic taste being thoroughly conventional with a marked preference for art that was derivative and psychologically concrete.

For Hitler and much of his beloved sanctimonious Völk , modernist art truly was degenerate, the plaything of the urbane and effete elite. Mangan cites the scholar Wilfred van der Will : “the purity of life before it became depraved by the sophistication, cultural corruption, social disunity and decadence of overcrowded urbanized civilizations” (126) as all that is wrong with the “big bad” city. To this day, conservatives often have an irrational fear of cities such as New York and Los Angeles, imagining them as teeming with “undesirables”: Jews, gays, the homeless, black folk, and foreigners- best to sit home smug and safe with Fox news blaring at full volume.

Hitler, with his ardent desire to promote a new nationalist identity, one far removed from the excesses of the Weimer Republic, sought to destroy the “false” idealism of progressive modernism. For as Barron attests, the work exhibited in the 1937 Entartete Kunst exhibition “reflected life in the Weimer Republic (1919-33) and were displayed as concrete evidence that the Nazis had saved German society from Weimer’s onslaught upon all the moral values held dear: marriage, the family, chastity and a steady harmonious life.”(25). That sounds familiar.

It is important to note that the work exhibited as Entartete Kunst in the 1937 exhibition were in fact taken from German museums that were publicly funded. When the German public (for many, their first exposure to new art) saw what the “degenerate” artists had wrought and what their tax dollars had purchased, they were predictably outraged. And if they were not initially outraged, they were soon pumped up by the opening speech, given by Hitler’s favorite painter, the very smug Adolf Ziegler (quote from Barron’s catalog):

“We now stand in in an exhibition that contains only a fraction [much was burnt by Goebbels as“dregs”] of what was bought with the hard-earned savings of the German people and exhibited as art by a large number of museums all over Germany. All around us you see the monstrous offspring of insanity, impudence, ineptitude and sheer degeneracy. What this exhibition offers inspires horror and disgust in us all.” (45)

Ziegler , to Hitler’s right, at Degenerate Art exhibition, 1937

The Nazi propaganda machine was diabolically brilliant in exhibiting the looted work in as base a manner as possible : deliberately hanging the “deranged” work askew for maximum negative effect, deriding the work with snide commentary and incessantly ridiculing what had been spent to purchase the “masterpieces”. The self-satisfied Völk were all too eager to be just as outraged. Barron cites a then 17 year old Peter Guenther who made a trip to Munich in 1937 a few days after Entartete Kunst opened. He describes a scene that is chaotic and stifling in its bourgeois smugness, the great middling exposed to art they found to be as incomprehensible to them as it was to their Führer . Guenther, hailing from a progressive and aesthetically minded family, was taken aback by the contemptuous sarcasm buzzing about his ears. Art was being derided that he and his family had enjoyed for some time. He describes his experience as:

“…large numbers of people pushing and ridiculing and proclaiming their disbelief for the works of art created the impression of a staged performance intended to promote an atmosphere of aggressiveness and anger. Over and over people read aloud the purchase price and laughed, shook their head or demanded ‘their’ money back.” (38)

One can picture the knuckleheads very easily, chuckling at their own insufferable wit.

Hitler was unable to comprehend the revolution in art that was going about him and unable to bear the praises it was receiving. His contempt for high culture had a particular geographic fixation, Vienna. Morton Levitt in his essay Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics makes it clear that the visual arts weren’t the only expressions of culture he found galling. Amidst the Viennese glitterati he found his scapegoat. Levitt comments: “Hitler despised Vienna and wished to supplant its dominant position in Austrian culture”. What he found particularly irksome was the Viennese affection for the music of Brahms, “…he (Hitler) appears to have disliked Brahms in substantial part because Jews were amongst the composer’s principle admirers, Viennese Jews in particular.” Further on Levitt argues that Hitler’s disdain for Brahms was contrasted by an allegiance to Bruckner;in Hitler’s words:

Brahms was praised to the heavens by Jewry, a creature of salons, a theatrical figure with his flowing beard and hair and his hands raised above the keyboard. Bruckner, on the other hand, a shrunken little man, would perhaps have been too shy even to play in such society (176).

By anti-Semitic default Bruckner trumped Brahms. These two men of musical genius were entangled in the bitter web of an angry spiteful man.

Hitler was not content in merely despising what he could not comprehend, in a perverse way, credit is due, as he was a man of ferocious action. If his taste was at best, conventional, derivative and uninspired, he nonetheless saw himself as an aesthete and an arbiter of public taste. From the beginning art and the destruction of works deemed unsuitable was a priority. As mentioned above, Barron explains that upon being made chancellor, one of Hitler’s first actions was the public burning of books by contemporary authors (9) , more would follow. Literature and music were minor concerns, as a frustrated artist, the visual arts were what he fixated his attention upon. So much so, that according to Mangan, over the entrance door of his newly opened Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), one found this motto inscribed: “Art is a mission demanding Fanaticism” (130). The message couldn’t be clearer.

Fanaticism was made material within the gallery spaces of his new temple. From period photographs it is difficult not to be impressed by the galleries, natural light floods the space, illuminating the Teutonic offerings to best effect. When the Entartete Kunst’s companion exhibition Grosse Deutsch Kunstrausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition) opened on July 18th, 1937, the German public were able to behold what their leader found suitably uplifting. The New York Times art critic Holland Cotter in his review (link here: http:/http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/14/arts/design/degenerate-art-at-neue-galerie-recalls-nazi-censorship.html?src=xps&_r=0) for the 2014 restaging of Entartete Kunst at the Neue gallery in New York city described the approved works of the Great German Art Exhibition this way: “most of the art was locked into uplift-intensive academic styles of an earlier time”. Cotter further asserts, “…even Hitler seemed disappointed with the results.” If he was, it didn’t cool his vitriol.

One cannot discern disappointment from the speech he gave at the opening of the exhibition, he lauds the work and by extension his keen discernment in selecting much of the art displayed upon the walls and plinths. In total 600 paintings and sculptures meant to represent the best and the brightest of Aryan artistic society. From Barron’s exhibition catalog, Hitler declared on July 18th 1937:

“From now on-of that you can be certain-all these mutually supporting and thereby sustaining cliques of chatterers and dilettantes, and art forgers will be picked up and eliminated. For all we care, those prehistoric Stone-Age culture barbarians and art stutterers can return to the caves of their ancestors and there can apply their primitive international scratching.”

If as Paul Wood states in his The Challenge of the Avant-Garde that “Nazi art theorists regarded both academic genre painting and a monumentalizing form of classicism as more appropriate to the ideals of the Reich” (261), they failed to convince everyone in attendance. Once again, turning to the nascent aesthete, Guenther describes his visit to the Haus der Deutsche Kunst. He provides a less than glowing review, in particular concerning the work of Breker and fellow Nazi approved sculptor Josef Thoraks:

If as Paul Wood states in his The Challenge of the Avant-Garde that “Nazi art theorists regarded both academic genre painting and a monumentalizing form of classicism as more appropriate to the ideals of the Reich” (261), they failed to convince everyone in attendance. Once again, turning to the nascent aesthete, Guenther describes his visit to the Haus der Deutsche Kunst. He provides a less than glowing review, in particular concerning the work of Breker and fellow Nazi approved sculptor Josef Thoraks:

[They] held no appeal for me: on the contrary, I found them rather frightening. I thought that they were intentionally attempting to imitate famous Greek sculpture I knew from books, but they lacked the grandeur and quiet balance that I considered to be the hallmarks of that art. (34)

Josef Thorak

Kameradschaft (Comradeship)

plaster, location unknown, exhibited at Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung

The teenage Guenther was an astute observer seeing through the wolf’s woolen drag. Yet Breker and his ilk would embody the party’s ideals, that were according to Wood “technically conservative [and] derivative of the academic classical tradition…adopted as the official National Socialist art form and all manifestations of avant-garde art, not only Expressionism, were to be ruthlessly extinguished”(263). That had been Hitler’s nefarious plan.

However, as Barron informs the reader, the Degenerate Art exhibition drew over 2 million visitors in the course of only four months in Munich alone. Over the next thirty three years, as the exhibition traveled over Germany and Austria, it drew nearly one million more. As of the date of the publication of Barron’s exhibition catalog in 1991, the “popularity of Entartete Kunst has never been matched by any other other exhibition of modern art” (9). It might be a stretch to equate attendance with “popularity” but the fact that five times as many people visited the Entartete Kunst exhibition over art deemed kosher by their leader attests to the powerful draw of this work-whether it be reviled or revered, it packed them in. By establishing a new fascist classical ideal and ridding the Aryan world of the degenerate taint of modernism, Hitler was able to focus his attention to other symptoms of the disordered and the perverse.

Before the hard and fierce muscularity of what Mangan calls Breker’s “swelling and tightening” übermensch there was a gentler more pastoral incarnation of the Grecian youth. The work of Hugo Höppener, known as Fidus (1868-1948), mentioned briefly above, hailed from another era prior to the excesses of the Third Reich and his work reflected the idealism and values of the early 20th century naturists: progressive politics, environmental concerns, vegetarianism, nudism and free love. Hopper’s work offers a glimpse into an imagined pastoral past, one populated, as Mangan describes by “images of naked youth, sun and landscape [that] depict the life forces of the cosmos”. These are bucolic scenes populated with “figures that represent a concept of male beauty …which eventually became the typical Aryan image” (120). Fidus’ work would seem a natural for the Reich’s propaganda machine, iconic images that represented the light and purity of the Aryan race while simultaneously hearkening back to a pre-industrial paradise untainted by Juden-capitalist urbanity.

Fidus

Source: http://www.berlinischegalerie.de/en/collection/artists-archives/highlights/hugo-hoeppener/

Yet that was not the case, for although (disappointingly) Fidus was an enthusiastic party member, joining in 1932, he failed to receive official party support. According the Berlinische Gallerie Museum of Modern Art website, the “effusive expression of his images did not interest the Nazis”. Citing the Führer’s own words, Mangan asserts he was looking for a killing machine, desiring to “create a violent, masterful undaunted and cruel youth…neither weakness nor tenderness must be about him” (165). The lithe beauty of Fidus’ Arcadian ephebes appeared fey in contrast to these “cruel youths”. In fact by 1937 Fidus’ work was seized by the government and sale of his images was forbidden. Fidus and his work, in spite of party loyalty, would fade into obscurity; his work would not be rediscovered until the 1970’s by the hippie and psychedelic movements.

It could be argued that Hitler’s disdain for Fidus and his oeuvre was more complex than mere aesthetic preference. As Barron claims, there was a purge of artists “ who were mentioned or whose work illustrated in any of the well-publicized books on contemporary art …or in avant-garde periodicals”, such a media presence made them “easy targets for the National Socialists” (9-10). Hitler may have had a keen sense of “gaydar” as Fidus’ work has a palpable homoerotic aesthetic (as does Breker’s). Fidus was a regular contributor to the first gay journal Der Eigene (The Unique, 1896-1932); participation in such a publication would have certainly made his work entartete kunst.

Vol. 10 (1924-25)

Hitler’s homophobic crackdown applied not only to the arts but to the political arena as well. Much has been written concerning the Nacht der langen Messer ( the Night of the Long Knives), in which the openly homosexual Ernst Röhm, chief of the Sturmabteilung (SA) and his fellow gay comrades were murdered on July 1st 1934. Although Hitler ordered the murders, Barron argues Hitler “defended Röhm against attack by declaring that the latter’s private life was his own affair as long as he used some discretion”(29). Barron and other historians seem to agree that the murders were less a persecution of high ranking homosexuals and more concerned with a struggle for power.

Heinrich Himmler, leader of the elite Schutzstaffel (SS) was a driving force behind the purging society of homosexuality. For although, as Barron explains, the SS “represented itself symbolically as an idealized semi-nude male”, actual homoerotic attraction threatened Himmler’s “obsessional regard for respectability” and his “fear of sensuality encouraged him to magnify homosexual threat” (30). Himmler took pride in the fact that the SS was regarded as what Mangan describes as the “aristocracy of National Socialism” (162). Himmler boasted, “we were able to assemble the most magnificent manhood” (79). To Himmler homosexual men (according to Barron, lesbians were for the most part left unmolested) were perceived as a threat to the health of the society. Barron quotes Himmler in pining for a mythic past, recalling how their ancestral Teutonic tribal leaders routinely executed homosexuals by drowning, he explained the barbarism this way: “this was no punishment, but simply the extinction of an abnormal life” (30). For Himmler, any deviation from bourgeois respectability was a threat to the Aryan race itself.

Although bourgeois respectability was an aspiration of the National Socialists, there is little evidence that their political drive was motivated by, that most familiar companion to bourgeois sensibilities, Christian fundamentalism. Barron records that when Hitler took power on January 30th 1933, the German Evangelical League welcomed the seizure (30), yet much of Hitler’s agenda was far from orthodox. He would occasionally mandate policy meant to appease the religiously conservative, such as when, as Barron notes, he banned “so-called” pornography on February 23rd 1933; there was also the perfunctory pledge to curb prostitution (30). Yet in many instances he seemed to disregard the conventional Christian ethos.

Hitler wasn’t seeking a gentle Christian model, far from it. As stated above, his desire for “neither weakness nor tenderness” was a sharp rebuke to what Mangan emphasizes as “the central image of Christianity, a tortured male nude, a feminized man who has passively…accepted humiliation, punishment, and death”, such a concept was to be “contemptuously rejected” (112). Hitler sought not the Agnus Dei but instead pagan barbarism. Mangan points out that as part of the National Socialists agenda to re-categorize various national holidays, Christmas was declared the Winter Equinox (132). Such move today would drive the religious right into a conniption fit.

On July 18th 1937, Hitler indulged his taste for pagan spectacle with an outlandishness few had witnessed before. A massive parade and pageant Zweitausend Jahne Deutsch (Two thousand years of German culture) wound its way through the streets of Munich to celebrate Hitler’s Tag der Deutschen Kunst (German Art Day) and deify Teutonic accomplishment. From period photographs one can observe hundreds of participants, garbed and garlanded in Druidic robes of black and white, solemnly supporting barges heavy with quasi-religious nationalistic symbolism. Guenther recalls his reaction to the bombastic display: “to my surprise-the huge head of the Greek goddess Athena, carried by people dressed as ‘Old Germans’, but there were also figures of the Germanic gods and goddesses with the eagle Hresvelda” (36). In Hitler’s universe there was as little room for the Good Shepherd as there was for the gay or the Jew.

Source :http:/http://www.hausderkunst.de/en/agenda/detail/histories-in-conflict-haus-der-kunst-and-the-ideological-uses-of-art-1937-1955-2/

Hitler imagined a pre-Christian world populated by god-like men. There seems to be little commentary, in this author’s research, concerning Hitler’s interest in the female form, although it should be noted that one of the centerpiece paintings of his Great German Art Exhibition was the impressive (yet insipid) neo-allegorical triptych by Adolf Ziegler The Four Elements, which featured four chillingly attractive female nudes. As mentioned above, Ziegler was Hitler’s favorite painter and was made president of the Reichskammer der bilden der Kunste (Reich chamber of the visual arts)- hence his duty to make the insufferable comments at the Entartete Kunst opening. As indicated by Barron, Zeilgler’s status as Hitler’s darling ensured his paintings hung not only on the walls of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst but on the walls of the Führer’s private residences as well. But Hitler’s preference for the female form seemed a private matter; in the public sphere the heroic male nude was his primary emphasis.

Adolf Ziegler

The Four Elements

source: http://galleria.thule-italia.com/adolf-ziegler/?lang=en

Hitler was verbose in praising male pulchritude, Mangan quoting from Mein Kampf , makes this citation: “…my beautiful youth! Is there a more beautiful generation in the whole world? Look at these young men and boys! What material! It will be the foundation of a new world order” (56). Later in speaking to his favorite, and admittedly talented, architect Albert Speer, Hitler gushes once again: “what splendid bodies (herrliche)you can see these days…only in our century does youth approach through sport the ancient Hellenic ideals” (76). Hitler desired Hellenic grace but attained Spartan steel.

The interest of the Third Reich, and that of its leader, in the male form was best expressed in marble and bronze; actual flesh made them a bit anxious. Although Hitler would enthusiastically praise Breker’s work, work which as Mangan argues has undeniable “phallic power [where] fascist male nudity represented politics not pornography”(110). Like degeneracy, pornography may lie in the eye of the beholder. If Hitler had little qualm with bronze biceps he did have issue with nudism. Nudism/naturism had vexed German society prior to the Reich, some extolled its healthful virtues, and others declared it a corrupting force. Hitler, as was his wont, had little ambivalence concerning the lawfulness of naturism; Barron reports that proletarian nude bathing was proscribed soon after the National Socialists came to power. Same-sex frolicking (banned in 1935) was held under especially harsh scrutiny as such behavior might be in violation of the draconian anti-sodomy law, Paragraph 175 (28).

In the sphere of the military, similar restrictions were put into place. Major Hans Surén, Chief of the German Army School of Physical Exercise, was well known amidst the physical training set. He wrote the influential Gymnastik der Deutschen (German gymnastics) in 1938, which ran through several editions during the course of the Third Reich. One of Surén’s mandates was that all sports training be performed in the buff. As Barron notes, the presentation of the ideal Nordic demanded, “the skin…be hairless, smooth and bronzed” (28). If Surén’s dictates suggested forbidden sensuality, it did not go unnoticed. Dutton suggests:

Surén’s obsession with nudity, he insisted that his soldiers train naked and often had himself and his pupils photographed in the nude …[this]…did not endear his more extreme views to Hitler who banned naturist clubs…and was no doubt concerned at the homoerotic overtures of Surén’s training methods (207).

Nordic Eros cast in bronze, was sanctioned as architectural ornament, but had no place in the gymnasium.

Mangan emphasizes the argument that the heroic male nude can safely be gazed upon when chastely rendered in sculpted form, in “ presenting his magnificent body full frontal to us…this body has ultra smooth surfaces and iron hard muscles…as impenetrable as a suit of armor…the austere architecture of the body keeps desire safely at arms length” (18). If you say so.

Mangan isn’t the only scholar posing this thinly veiled homophobic anti-Eros stance. The neo-classical sculptor Jose Alvaros Cubero (1768-1827) was professing what Dutton refers to as “erotic numbness”, when the sculptor declared that “mythical statuary …is incapable of arousing sensuous pleasure” (288). That seems an incredible assertion given the undeniable sensuous appeal of the Venus de Milo, Farnese Herakles, and other classical works found in countless reproduced form. One questions if they were purchased solely for the sake of classical enlightenment.

If fascist society had established “safe” zones for gazing the male nude, in order not to corrupt the hetero-normative construct, one cannot deny the intense male bonding of the National Socialist party. From all appearances the S.S. was at least homosocial. Even Mangan seems to concede this point in describing the bond shared by the Schutzstaffel , based ostensibly upon a “love of country” which manifested itself as “eroticized nationalism”. He further argues that nationalism is particularly vulnerable “to a distinctly homosocial form of male bonding”(172).

From the literature this author has researched, there seems to be little willingness from academics to consider that this homosocial nationalistic male bonding, and the highly eroticized visual culture used to promote the aspirations of the National Socialists, is in anyway actually homosexual in nature. Mangan, perhaps revealing a heterosexist bias describes Breker’s work as “exud[ing] a bleak passion that is neither hetero-nor homo-erotic, it is political. It is sublimated sexuality…”(141). This author questions that assertion, for although Breker (and his ilk) created “bleak” gods, hard and fierce, they nonetheless possess an erotic appeal-at least to a great many homosexual men. Mangan , quoting Susan Sontag, who in discussing the films of Leni Riefentahl’s National Socialist’s films Olympia and Triumph of the Will makes a salient point that can be applied to Breker’s work and the impact it has upon contemporary sensibilities : “it is dishonest…to say that one is affected by the Triumph of the Will or Olympia only because they were made by a film maker of genius. The truth is, she asserts, that the films are still influential because ‘their longings are still felt’”(133). In spite of nationalistic excesses, the work of Breker reveals an artist possessing a degree of genius; his work may have sublimated desire, but to those attuned to it speaks loud and clear.

still from Riefenstahl’s Olympia

Arno Breker

Der Sieger

1939

In the end, there is not hard evidence that Hitler harbored latent homosexual desire- in fact this author believes he did not. Much of what we can gather about Hitler and the National Socialist Movement is from the material culture left behind. To the modern eye (to this observer’s particularly), Hitler’s fawning over the magnificence of Aryan youth and his fervent embrace of Breker’s bombastic übermensch raises suspicions. From a psychological perspective, one might suggest that Hitler’s self loathing, fueled by an unrelenting sense of indignation and envy, led him to destroy all that he found confounding, belittling, or threatening, be it “degenerate” art or a “degenerate” person.

In the end, Hitler failed at his mission. He sought to quash Modernism (and what it represented) and replace it with a parody of Academic Classicism, but his vision is seen as flaccid, and instead collective society disparages much of what he held in such esteem; Breker’s pastiches bombed and the Degenerates triumphed.

In conclusion:

As the smoke cleared, in the wake of the Second World War, and as nations sought to heal, monuments to the fallen began to appear far and wide, in any place chilled by Ares’ shadow. One such monument is particularly dear to this author’s heart, the thirty nine foot monumental bronze memorial Angel of the Resurrection (1952) by Walker Hancock (1901-1998), located pride of place in the magnificent lobby of Philadelphia’s Thirtieth Street railroad station. The monument commemorates fallen soldiers who had been railroad employees; the base is inscribed with these words:

IN MEMORY OF THE MEN AND WOMEN OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD WHO LAID DOWN THEIR LIVES FOR OUR COUNTRY 1941-1945”

and “THAT ALL TRAVELERS HERE MAY REMEMBER THOSE OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD WHO DID NOT RETURN FROM THE SECOND WORLD

It seemed strange to this author that there would be that many casualties to just one institution, the Pennsylvania Railroad, yet such were the losses, and the sentiments expressed, that such a lavish and costly monument was warranted.

The monument itself warrants observation in light of the topic of this paper, for Hancock, like Breker, worked within the academic tradition. Hancock also employed a similar aesthetic (Sontag referred to the Angel of Resurrection as “faintly lewd”; it isn’t lewd). Hancock, in his civilian life was an instructor of sculpture at the esteemed Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. During his time as a soldier he had been a Minute Man, one of the enlisted who recovered art looted by the Nazis. It is a fitting conclusion to this paper to close with Hancock as a contrast to Breker. Hancock, classically trained, synthesized the ideals the National Socialists aspired to, crafting a monument infused with grace, possessing deep pathos and stands as a testament to sacrifice and regeneration.

Walter Hancock

Angel of the Resurrection

Works Cited

Barron, Stephanie, ed. Degenerate Art :the Fate of the Avante Garde in Nazi Germany. New

York: Abrams, 1991. Print.

Cotter,Holland.“First They Came for the Art : ‘Degenerate Art’ at Neue Gallery, Recalls Nazi

Censorship.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times Company, 13 Mar.2104. Web.

15 apr. 2015.

Dutton, Kenneth R. The Perfectable Body: The Western Ideal of Male Physical Development.

New York: Continuum, 1995 .Print.

“Fidus/Hugo Höppener(1868-1948.” Berlinischegalerie.Berlinische Galarie of Modern Art.

- Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

Levitt, Morton.”Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics.”Journal of Modern Literature 26.3/4

(2003):175-178.Web.15Apr.2015.

Mangan,A.J.,ed.Shaping the Superman:Fascist Body as Political Icon-Aryan Fascism.Portland:

Frank Cass,1999.Print.

“Pennsylvania Railroad World War II Memorial.”Wikipedia.Wikimedia Foundation,

4 Feb.2015.Web.15 Apr.2015.

Speiler,Richard.Max Beckmann:1884-1950 The Path to Myth.Los Angeles:Taschen,2011.

Print.

Wood, Paul, ed. The Challenge of the Avante-Garde. New Haven: Yale UP, 1999. Print.